I have recently been interviewed Who-Is-Agile-style by Sergey Kotlov, the leader of the Agile St. Petersburg community. This post is the English translation of the inteview’s Russian original.

I am thankful to Sergey for this opportunity and being a great copy editor.

I met Alexei virtually when we translated Olav Maassen and Chris Matts’ Commitment book. As a result of our collaboration, one of the most important Agile books of the last several years will be available in Russian. All that remains to do is to print it. If you’d like to help us with that, write to us (or leave a comment to this post).

I was quite surprised when I found that Alexei is from St. Petersburg originally, even though he has lived in Canada for a long time. I couldn’t miss an opportunity to interview him, considering that he has recently been accepted into the ranks of Lean Kanban University (LKU), an international professional organization dedicated to Kanban. If I’m not mistaken, he is the first Kanban Coaching Professional (KCP) from the former Soviet Union.

What is something people usually don’t know about you but has influenced you in who you are?

First of all it’s my school where I and my classmates got a positive charge to last a lifetime: to keep learning, discovering new abilities and trying to be the best at what we do. I suspect I and the kids I went to school with were not alone at that. I believe many Russians who read stuff like Who Is Agile? went to a similar school or experienced something similar in university.

I also studied music for quite some time and that taught me to be attentive to detail in my work and also to change my repertoire often. Nowadays when I give consultations on IT process improvement, my material and methods are updated significantly over a short period of time.

If you would not have been in IT, what would have become of you?

The same, because I was not in it. I was interested in developing new products and technologies at the time. IT was about using what was already available.

People often call IT anything that has to do with computer technologies, but the distinction was very clear for a long time. People who worked on requirements, design and coding usually didn’t have access to the servers executing their code. People who “were in IT” were the ones who had access to the data centres where those servers were located. They used completely different knowledge and skills to develop this IT infrastructure. On the other hand, we wouldn’t let them near “our” source code. Then the two worlds began getting closer – we now call it DevOps.

Having made the journey through Agile to Lean, I got a chance to give consultations to IT specialists fighting fires in their data centres (just like in The Phoenix Project) and help them improve their processes with Toyota Kata and A3. We’ve come full circle to (Lean) IT. So, what if — I would have gotten the same thing.

What is your biggest challenge and why is it a good thing for you?

Putting my thoughts in writing. There is no chance to react to my audience’s reaction and correct what I’m going to say next. My written monologue will most likely not lead to the same level of understanding as a live dialogue. I have to choose my words carefully and that’s difficult.

Why is this a good thing for me? Daily practice.

What drives you?

“The stewardship of the living rather than the management of the machine”, the words from the Stoos Communique (see also: the group of 21), which resembles the Agile Manifesto and the Declaration of Interdependence, but it says more explicitly that processes of intellectual, creative work as well as ways to improve them ought to become more humane. This is in everybody’s interest: customers, company owners and, of course, workers who come to do their job day in and day out.

You can hear even from progressive Agilists: “a transformation plan”, “to build a process”, “to implement a new methodology”, etc.* – catch yourself and others when you hear it! This is the “management of the machine” language: a machine can be taken apart, put back together, installed, moved from one shop floor to another, changed over. But human organizations, where product development, IT projects and other knowledge-work activities take place, are not machines, but ecosystems that need to evolve organically.

(*-I picked three phrases from original Russian Agile sources as examples; their direct translations may not be the best examples of the mechanistic process change jargon in English – A.Z.)

What is your biggest achievement?

I don’t think it makes sense to list any moments of success or choose one of them. Whatever they might be, they will be surpassed by my children.

What is the last book you have read?

From Russia to Love, a biography of Viktoria Mullova. When I studied music, our teachers held her up as an example (she won the 1982 Tchaikovsky Competition). I don’t recall them doing it any longer though after she defected from the Soviet Union to the West during a concert tour. The book is about how people learn, pursue mastery and, even after accomplishing a lot, still find new goals and paths towards perfection.

I read a lot on my professional interests, both books and blogs, as well as books that can lead me to useful ideas obliquely.

What question do you think I should also ask and what is the answer?

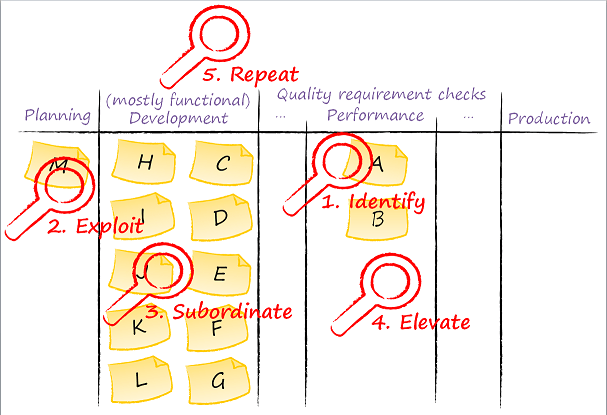

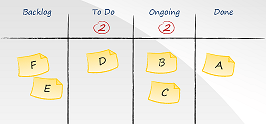

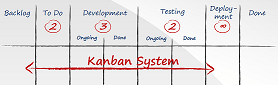

The question would be about the literature and a list of useful sources on Kanban. Of course, we’re not talking about organizing a visual board in your office, which is easy to do, but about understanding Kanban deeper. What do experts know and where do they find the ideas they present to us?

I created a list to answer this question. It is not a complete list by any stretch, but is a good foundation. I tried to include the books containing ideas already internalized by coaches (especially those recognized by Lean Kanban University) who use them effectively to guide evolution of processes and organizations. I am sure there are those in Russia who are interested in this stuff; they can write to me and I’d be happy to discuss these ideas and their practical applications.

What do you think is missing in the St. Petersburg Agile community and how to change it?

We are missing an internationally-recognized expert, author and leader, who would also be an excellent organizer of conferences and communities. Someone like Arne Roock (LinkedIn, blog) from Hamburg. Possibly, he or she will step up eventually.

Who should be the next person to answer these questions?

I’d like to name three people. Denis Khitrov knows business and innovation, because he’s been doing that for years. This is exactly where our methods, Agile and whatnot, ought to make impact. His latest venture MedM, at the intersection of medicine and mobile technologies, has just brought home to St. Petersburg the main prize from Skolkovo, beating 800 other startups for it. Also, talk to two Nikolais – Shevelev and Pultsin.